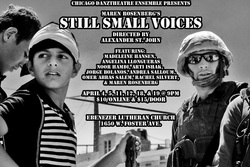

Interview with Alexander St. John, Director of Still Small Voices Lauren: Could you tell me how you got involved with Still Small Voices? Alex: Back in December Maren Rosenberg, the playwright, came to me and asked if I would direct the play. She’d done this show in 2009 in Michigan where it premiered at the Boar’s Head Theater. She had been in the West Bank for about two months. She wanted to write a play about it, tell people about her experience. That was the first version. Then she went back to the West Bank for two and a half years and in that time she toured the show there in Arabic. Then she came to me in December asking me to do it for April, wanting me to revamp the script. The first two versions had more of an Alice in Wonderland framing so it was a little different from what we are doing. It was the idea of this Jewish-American girl going and being lost in this interesting world and involved with different characters. It was an interesting metaphor at the time but since they’ve released a movie and there have been so many pop culture things with Alice in Wonderland in the last few years, we wanted to move away from that. So she came to me with two scripts and boxes of journals and diaries and she just gave them to me. And I looked through it all and we reworked the whole script together. So we basically rewrote a whole new play. We kept the stories of the people she encountered and that’s what’s been put into this and so it’s become more her story. Because when she was in the West Bank, she met a guy, she got engaged to him. She’s Jewish. He’s Muslim. He’s Palestinian. So it’s this interesting love story that came out of this, these conversations but she was so scared to put her own story out there. Lauren: So the inspiration came from her own story. Alex: And I kind of pushed her into writing it. Lauren: This version you are doing, how different is it from the version performed in Michigan? Alex: We kept some monologues and certain characters and stories she was connected to but we totally changed the structure. It was a collaborative process of me telling her what was most interesting and what, as an American, appealed to me to understand the culture more and show how these two cultures converged in her experience. But we also took the meat from the original plays. It’s totally her journey. You are taken on the journey with her. There’s a conversation with her sister back home about the birthright trip. So birthright is something that the Israeli government has set up to get Americans and Jewish foreigners from all over the world to come to Israel, to their homeland. To get young Jewish foreigners to come there and possibly come live in Israel and add to the majority. You go there for ten days, it’s completely paid for. A lot of people do it, it’s a good experience. But Maren went she wondered, “What’s going on on the other side of this wall? What’s going on in the West Bank?” And basically her curiosity lead her to Palestine. So she went there, she saw it and she wanted to stay. And that’s what the story is about. Lauren: So she approached you about directing the show in Chicago? Alex: Exactly. She knew she wanted to do this show for April with Chicago Danztheatre and she had seen a show I had directed back in the fall and because of the style of my work knew that I would be a good fit. It was with a company that Maren is also a member of called Halcyon Theatre and it was a choreo play that I directed. It was a very movement, lyrical play. She said this would be great for her play- this kind of aesthetic. Lauren: Are there any dance elements in this play? Alex: Definitely, there is dancing, singing. They perform a poem. We perform a really famous poem by Mahmoud Darwish called “Identity Card.” So it’s still very interdisciplinary like Chicago Danztheatre is. There’s projections, video. All sorts of stuff. It’s kind of… I don’t want to say circus, but there’s a lot of elements going on. It’s definitely a spectacle for sure. Lauren: What do you want to give to the audience? Alex: I hope people go in with more empathy, understanding the conflict- that it’s not completely black and white- that there isn’t a totally right or wrong perspective. And understanding the Palestinian side of things a little more. Because you don’t get to see that in the news here and it’s kind of glazed over in a lot of things. And also to kind of break people’s personal biases or point of views. I think a lot of people, in this country especially, have these biases to think that somebody who wears a hijab is immediately a terrorist, or that they’re wrong, or that someone who’s Muslim is a threat. I want to help break down these ideas to people- to understand that they have the same desires, wants and needs as anyone else. I think there’s a lot of prejudice towards Middle Eastern cultures that is really irrational. A play like this helps people understand, “Oh, they have a family just like us. They have brothers and sisters just like us.” Lauren: Has anything changed for you, working on this play? Alex: I’ve learned a lot. I, when I first came into it, told her that I was full-force about doing it but I didn’t really have an opinion about the conflict. I was still a very neutral perspective because I really did not feel educated enough about it to make a strong decision. From the time I started working on it with her, back in December/January, I was like, “Wow! This is horrible what is going on.” And I started realizing the depth of it. I had known from my own experience of friends who had done art projects on it, but I had never really delved into it myself. The second I started to was when I really realized that what was going on to this group of people and this culture was systematically wrong. This kind of ethnic cleansing that I just don’t agree with and think is horrible. It was really eye-opening for me at first. At first I was really neutral- “It’s political, I don’t want to get too on one side or the other.” As time goes on I feel that, no, people can be offended by this work. They can be mad at me for doing this because I believe in it. I believe that what is going on over there is wrong. What really connected to me was when I started watching documentaries and listening to people talk about it. All these people talked about the land and how their families and generations were raised on this land and it’s where they are from. For me, I have a big family, I come from a family that’s not rooted in American identity, but rooted in, “This is our home. This is where we belong.” If somebody all of a sudden came along and told me, “This isn’t your home. You’re not allowed here,” that would be heartbreaking. That is what I connected to the most- what it means to connect to the land and the physical place you are from. I’m from New England. I think of the mountains and the woods. If somebody came to me and said, “This isn’t yours, you can’t identify with this,” I don’t know what I would do. Lauren: Have you ever worked on a piece that was controversial like this? Alex: I think most of my work is. Most of my work is very race, class-oriented to begin with. Back in December one of the projects I did was re-envisioning Tennessee William’s Sweet Bird of Youth. And that’s a play that’s typically with an older white woman and a younger white man. I did it with an older white man and a younger black man. So I created the conversation of issues within the gay community but also racial issues in general and generational issues. There’s a lot of that that I explored. The project I did in the fall that Maren saw was a play about the African American woman’s experience in America. Specifically about finding inner peace and acceptance in yourself in a society that’s constantly telling you that you don’t fit in, you’re not a majority, you’re not mainstream. And also generational differences as well. What happens each generation when you’re- I don’t want to say minority- when you’re an underrepresented person in a society when you’re not a part of the mainstream. What happens to try to blend in instead of embracing their heritage. It happens with anybody who is seen as not a part of the mainstream. You either blend in or you go against that and are seen as combative, as a problem. I think all my work deals with that. Lauren: How did you get involved in theater? Alex: I’ve been doing theater since I was about five. It’s always been my medium of choice. But then I think the college I went to really informed the work I do now. I went to Bennington College in southern Vermont. We didn’t have grades or general requirements. You designed your education. But it’s also a very activist/progressive school. I was always very outspoken. I grew up in Connecticut but we moved to the south when I was about ten, eleven. My parents were super liberal, hippies. They said, “You don’t have to be Baptist. You don’t have to be religious. You don’t have to be embrace the conservative culture here.” So we were already very outspoken people to begin with, but where I went to college solidified that for me as an artist and doing work that has meaning and value to it and has a message instead of doing work to be pretty or reflective of mundane issues that don’t mean anything. So much theater is done for this older, white upper-class that pays for it. So then we do so much theater for that instead of representing people that aren’t seen and issues that are really going on in our society. For me, the reason I make art and do theater is to create change. A lot of material seems reflective of society without questioning it. I want people to walk away from my work questioning things- what’s right and what’s wrong and the way that they view the world. A lot of work can be narcissistic and reflective of feelings but not feelings about the world you live in, feelings about the personal self- ego. So much theater feeds people’s ego to keep being who they are instead of looking at the bigger picture! Is there a way that I can help problems, fix them or just not be a part of them? I do a lot of work that touches base with mental health and de-stigmatizes it. Another project I do with Chicago Danztheatre is about veterans. What happens to veterans when they come back? Some of them have mental health problems, don’t fit in or commit suicide. So how do we re-integrate these people and make them feel like they are a part of society after this traumatic experience? With Vietnam vets that’s a huge issue. They came back and everyone just hated them and they felt guilty for this thing that they were doing for their country. So bringing awareness to issues like that, too. Lauren: What else would you like people to know about the show? Alex: What do I want? I want people to come see it because there aren’t a lot of plays about this right now. But that’s not the only reason. I want people to be able to experience a different perspective that maybe they haven’t thought clearly about or considered. Because even in our media you aren’t given a clear perspective. In this play, you get to see people on stage interact with each other that come from different backgrounds and how they learn to connect. And it’s not that difficult. It’s through talking, listening and finding common ground. Finding commonalities which every person should be able to find with someone else who’s a living person. I think for me, especially in this play it’s also the representation of Palestinian culture and Arabic-speaking people in general. There’s a lot of Arabic in the show and we are doing a lot in Arabic with English subtitles. Having that representation on stage is really rare, right now, and I think really important. I think bilingual theater, non-English-speaking theater, is very effective sometimes. Because you can see these people communicate in their native language. There’s a wonderful quote from Nelson Mandela that’s, “Speak to a man in a language he understands and that goes to his head. Speak to a man in his own language and that goes to his heart.” And I think that’s a lot of why I really pushed Maren to incorporate Arabic and Hebrew, as well. Lauren: What you say about connection makes me think that, in part, it is about finding common ground, but also it’s about raising those questions, raising conflicts. That can connect, too. So often we spend time with people who think the same way. Being with somebody where we have different ideas can be connective too. Alex: Exactly. The people I’m working with, we all kind of have the same side, but we all come from such different background and cultures and have come to understand and appreciate each other. Because you were raised Muslim and I was raised without religion does not mean we cannot be friends. Just because somebody wasn’t raised in the same system or structure as you doesn’t mean you can’t connect. That’s a lot of what this play is about. Overcoming lots of fears and prejudices. These ideas that have been engrained in us and we haven’t really considered if they are true. I’m hoping this brings a lot of people together as well, just in the audience. That it really brings different perspectives so that they can be changed in all different ways. Not just Americans coming to understand Palestinians more but Palestinians coming to understand Americans more, too. I think that’s important. It’s a really great group of performers. It’s just a really unique group of people who have come together and are passionate about it. I thought it was going to be really hard to find these people but it hasn’t. It’s been a good time so far.

5 Comments

|

Archives

April 2021

|